You often read about how thanks to the internet, our cultural identity is more fragmented than ever. And to some extent that’s true. Thanks to the reduction in gatekeeping and distribution costs, we have more choice than ever. We live in an age of abundance. But it turns out our tastes are mostly the same. Or rather, we still find ourselves coalescing on the same cultural touchstones, or “Schelling points” if you want to be @ballmatthew about it.

Increasingly that cultural Schelling point is the Netflix top 10 list.

It may seem funny that a service, built at least in part on the premise that the internet creates stores with limitless shelf space, is in effect, funneling attention into the products visibly displayed in the end caps or behind the cash register but the reality is that despite all of our technological progress, humans simply do not have more time, nor more ability to sift through information than we did before. We just have more of it.

We are fundamentally lazy and as such, increasingly the most valuable products or businesses in the world are predicated on reducing that cognitive friction and making those choices for us. But beyond that, we are also fundamentally happier being in a group than out on our own. So more than just being useful then, the top 10 list, I suspect, is fundamentally comforting on some level for those of us increasingly paralyzed by choice, which is to say nearly all of us.

All this is pretty well known and often discussed, usually by VCs or tech executives touting why the big tech companies are both driving monopolistic value but also somehow not monopolies at the same time because we have infinite choice and we choose as opposed to being forced to use them. But what is less often discussed, is the second-order impact of this on our general culture and economy.

As the internet creates endless niches, our tendency towards simplification and safety in numbers is flattening differences and aggregating behavior, just in a more rapid fashion than ever before and at a far greater scale. Whereas we have always been fad-driven, group think prone actors, our fads and cultural trends used to take time to percolate, develop, build, reach meaningful scale and then pop. Now, thanks to the power-law dynamics of digital distribution, we can go through all these steps, and reach a never before seen global scale, at the blink of an eye.

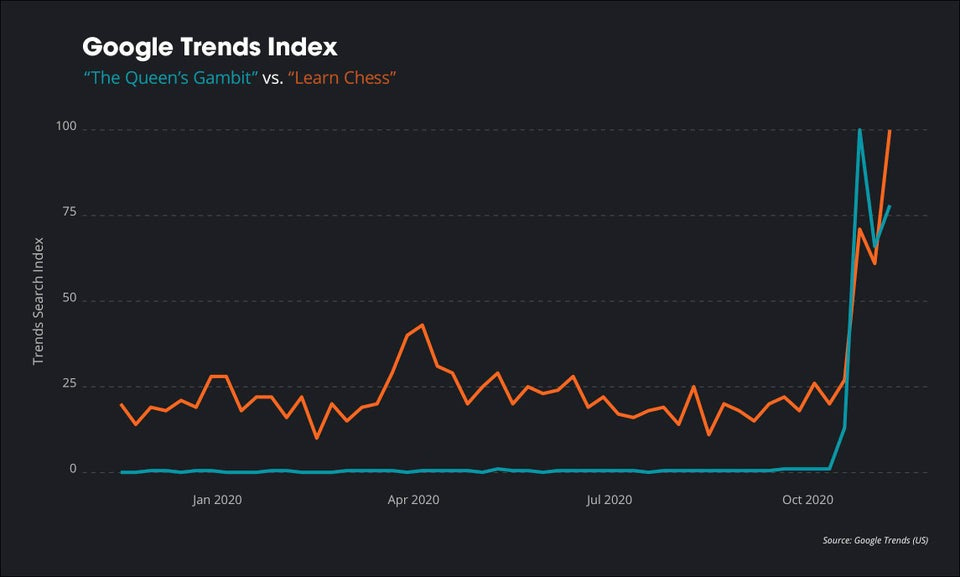

Just look at the rise and fall of your favorite Tik Tok trends. Every day is a Groundhog day repeat of February 26th, 2015, the day when the internet gave us a dress that was both blue and black and yellow and gold along with two llamas that seemed to own all of our collective attention. And so, in a purely predictable fashion, a popular Netflix show about chess means we are all learning to play the Queen’s gambit.

So what does this mean for us? I think it means we only see more and bigger fads at faster paces. That we have more diversity than ever, and yet somehow less at any one point in time. It also means that increasingly the real value or trick won’t be in blowing up, though of course, it will only get harder and harder to do so as we continue to exponentially increase our output of content, but rather in holding on to the 15 seconds of fame once we have it.

As such, the shift towards consumer subscription businesses, continuously updating free-to-play games and ever-expanding cinematic universes is not only a driver of this cultural phenomenon. It is also a reaction to it: a desperate attempt to hold on to what is increasingly impossible to get in the first place, attention. Every VC and executive has been trained to ask about and judge businesses based on their go-to-market and distribution strategy but perhaps they should start focusing on their stay-in market and retention strategy more deeply.

I also suspect that it means some of us and some businesses will learn to accept that fame comes 5 seconds and not 15 minutes at a time and punt entirely on the idea of retaining it. Instead, focusing on harvesting and capturing as much as possible. Some will embrace the increasingly transactional and faddish nature of our cultural society and simply become repeat 1-hit wonders.

In business, MSCHF seems to be leading the way here. I’m sure there are individual creators doing so as well. And in our personal lives, look no further than our behavior with respect to dating and friend relationships; where on the one hand we have deeper, more integrated, more communicative relationships, on the other we have more and more shallow, fleeting, explosive connections than ever.

All of which is to say that by the time you read this, Queen’s Gambit will likely no longer be relevant, we will have all stopped playing chess and I’m probably out here writing about some new trend as if it will be here to last while desperately trying to convince you to stick around for my next post.

Credit to u/nickkuiper11 who posted the chart on r/dataisbeautiful